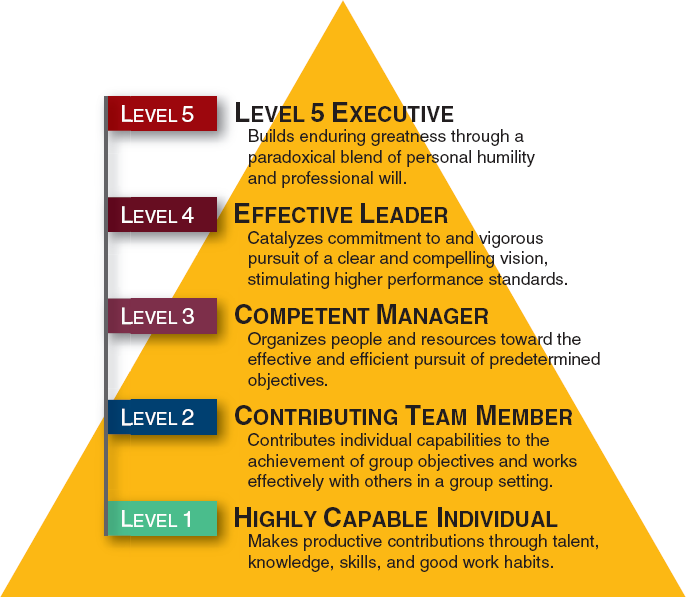

In his best-selling book Good to Great, business author and former Stanford professor Jim Collins tried to pinpoint the traits that define “Good-to-Great” companies, i.e. “fifteen-year cumulative stock returns at or below the general stock market, punctuated by a transition point, then cumulative returns at least three times the market over the next fifteen years.”[1] One of the traits that lead to organizational greatness, according to Collins and team, is “Level 5 Leadership”: “a paradoxical blend of personal humility and professional will.”[2] The latter speaks of unwavering determination and resolve, but it is the former that is perhaps the most unique of the two. “During interviews with the good-to-great leaders, they’d talk about the company and the contributions of other executives as long as we’d like but would deflect discussion about their own contributions…It wasn’t just false modesty. Those who worked with or wrote about the good-to-great leaders continually used words like quiet, humble, modest, reserved, shy, gracious, mild-mannered, self-effacing, understated, did not believe his own clippings; and so forth.”[3] Though Collins identifies humility as a positive trait for leaders and their organizations, the why and how of its positive effectiveness is left murky (as is its definition).

In his best-selling book Good to Great, business author and former Stanford professor Jim Collins tried to pinpoint the traits that define “Good-to-Great” companies, i.e. “fifteen-year cumulative stock returns at or below the general stock market, punctuated by a transition point, then cumulative returns at least three times the market over the next fifteen years.”[1] One of the traits that lead to organizational greatness, according to Collins and team, is “Level 5 Leadership”: “a paradoxical blend of personal humility and professional will.”[2] The latter speaks of unwavering determination and resolve, but it is the former that is perhaps the most unique of the two. “During interviews with the good-to-great leaders, they’d talk about the company and the contributions of other executives as long as we’d like but would deflect discussion about their own contributions…It wasn’t just false modesty. Those who worked with or wrote about the good-to-great leaders continually used words like quiet, humble, modest, reserved, shy, gracious, mild-mannered, self-effacing, understated, did not believe his own clippings; and so forth.”[3] Though Collins identifies humility as a positive trait for leaders and their organizations, the why and how of its positive effectiveness is left murky (as is its definition).

Bradley P. Owens, then assistant professor at the State University of New York at Buffalo (now Assistant Professor of Business Ethics at BYU), has conducted some of the most in-depth studies on humility and its impact on organizational outcomes.[4] Owens and colleagues developed a model they call “expressed humility” by focusing their attention “on the expressed behaviors that demonstrate humility and how the behaviors are perceived by others.”[5] They define “expressed humility” as follows:

an interpersonal characteristic that emerges in social contexts that connotes (a) a manifested willingness to view oneself accurately, (b) a displayed appreciation of others’ strengths and contributions, and (c) teachability.[6]

After taking care to distinguish via testing the difference between humility and other similar traits,[7] Owens then looked at the effects leader-expressed humility has on organizational outcomes. The results revealed that leader-expressed humility is positively related to team learning orientation and thus fosters a group climate of learning and development. This intrinsic orientation toward learning leads to increased employee engagement. Furthermore, leader-expressed humility was found to be positively correlated with employee job satisfaction and therefore negatively related to voluntary employee turnover.[8] When a leader is humble, employees are more oriented toward learning and more fully engaged in and satisfied with their work. This means that fewer individuals voluntarily leave the organization (i.e. low turnover).

The above is a breakdown of how leader-expressed humility impacts subordinates. The why is linked to the leader’s role in team learning:

Leader humility at the most basic, fundamental level appears to involve leaders catalyzing and reinforcing mutual leader-follower development by eagerly and publicly (i.e., outwardly, explicitly, transparently) engaging in the messy process of learning and growing. Even more simply put, humble leaders model how to grow to their followers. Rather than just talking about the importance of continual learning or supporting programs for followers’ development and growth, humble leaders transparently exemplify how to develop by being honest about areas for improvement (i.e., acknowledging mistakes and limitations), encouraging social learning by making salient the strengths of those around them (spotlighting follower strengths), and being anxious about listening, observing, and learning by doing (modeling teachability).[9]

Drawing on 55 in-depth interviews, Owens found that “followers viewed their leader’s humble behaviors as legitimizing followers’ own developmental journeys, leading to follower psychological freedom and engagement; and these humble leader behaviors were seen as legitimizing contextual uncertainty, leading to a preference for small, continuous, rather than large, discontinuous, changes and fluid organizing (i.e., ease and swiftness in transitioning to different ways of functioning).”[10] Humble leaders model “how to be effectively human rather than superhuman” and “legitimize the actual process of becoming. In other words, the core impact of leader humility on followers appears to be followers’ constructive and adaptive responses to their own inexperience, gaps in development, and mistakes. By helping to reduce follower anxiety and evaluation apprehension during the process of development, humble leaders help free up followers’ psychological resources to be used toward more productive ends.”[11]

In layman’s terms, humble leaders show that it is alright to be imperfect. One doesn’t have to know everything. Leaders don’t either. One can make mistakes. Leaders do too. These humble leaders are learning and growing right alongside everyone else. Free from the fear of failure and the impossible goal of perfection, organizational members can focus on what’s important. And they become engaged and productive members because of it. Not only does this benefit individual members, but the organization as a whole.

In the Saturday session of the October General Conference, President Uchtdorf made headlines with the following regarding those who separate themselves from the LDS Church:[12]

Sometimes we assume it is because they have been offended or lazy or sinful. Actually, it is not that simple. In fact, there is not just one reason that applies to the variety of situations.

…Some struggle with unanswered questions about things that have been done or said in the past. We openly acknowledge that in nearly 200 years of Church history—along with an uninterrupted line of inspired, honorable, and divine events—there have been some things said and done that could cause people to question.

Sometimes questions arise because we simply don’t have all the information and we just need a bit more patience…Sometimes there is a difference of opinion as to what the “facts” really mean. A question that creates doubt in some can, after careful investigation, build faith in others.

And, to be perfectly frank, there have been times when members or leaders in the Church have simply made mistakes. There may have been things said or done that were not in harmony with our values, principles, or doctrine.[13]

Movingly, President Uchtdorf said to those who have left and/or are struggling,

To those who have separated themselves from the Church, I say, my dear friends, there is yet a place for you here. Come and add your talents, gifts, and energies to ours. We will all become better as a result…There are few members of the Church who, at one time or another, have not wrestled with serious or sensitive questions. One of the purposes of the Church is to nurture and cultivate the seed of faith—even in the sometimes sandy soil of doubt and uncertainty.[14]

While I think it would be a stretch to call this a “new direction” in Mormonism,[15] President Uchtdorf’s address was nonetheless an expression of humility.[16] In what Terryl Givens has called “one of the most centralized, hierarchical, authoritarian churches in America to come out of the era famous for the ‘democratization of religion’,”[17] it is easy for members to perceive their fallible leaders as quasi-celebrities or even quasi-deities. This has been a problem dating back to Joseph Smith. As Givens explains,

[Joseph’s] insistence that his pronouncements did not always carry prophetic weight was not just a safety net or a convenient means of prudent retreat if things didn’t work out. It meant that the process, the ongoing, dynamic engagement, the exploring, questing, provoking dialectical encounter with tradition, with boundaries, and with normative thinking should not be trammeled by or impeded with clerks, scribes, and disciples looking for a final word, interrupting a productive process of reflection, contestation, and creation…In other words, Joseph’s concept of revelatory process paralleled his concept of salvation itself, both being construed as products of ceaseless struggle through which we must engage the universe…[18]

If LDS leaders are concerned about the organizational health of the Church (as they no doubt are), then Uchtdorf’s humble acknowledgement of this “ongoing, dynamic engagement” in General Conference was certainly an act of inspiration. Humble leadership can heal many institutional problems. This kind of leadership by example has been taught and canonized since the early days of the Church: “We have learned by sad experience that it is the nature and disposition of almost all men, as soon as they get a little authority, as they suppose, they will immediately begin to exercise unrighteous dominion…No power or influence can or ought to be maintained by virtue of the priesthood, only by persuasion, by long-suffering, by gentleness and meekness, and by love unfeigned” (D&C 121:39, 41). David Whitmer’s late recollection of the Book of Mormon translation process recalled an instance in which Joseph Smith was “put out about…something that Emma, his wife, had done.” This anger and frustration prevented Smith from being able to “translate a single syllable.” It was only after he “made supplication with the Lord” and “asked Emma’s forgiveness” that “the translation went on all right. He could do nothing save he was humble and faithful.”[19] Joseph was often working side-by-side the saints in the literal building of Zion. Most of us today do not see General Authorities on a daily basis. Uchtdorf’s address may not necessarily be a better example of humility than in times past, but perhaps better suited for the modern global church.

President Uchtdorf recognized past mistakes of leaders. He acknowledged that questioning and uncertainty are understandable and commonplace within the Church. He noted the limitation of available knowledge and information. Most important, he displayed a desire and appreciation for the members’ “talents, gifts, and energies.” Uchtdorf’s expressed humility has resonated widely with members of the Church. The anxieties of many have been quieted and replaced with a desire to more fully engage in the process of growing, learning, and furthering “the work.”

I hope this expressed humility is something we can expect in future General Conferences. It might help us with our own.

NOTES

1. Jim Collins, Good to Great: Why Some Companies Make the Leap…And Others Don’t (New York: HarperCollins), 6.

2. Ibid., 20.

3. Ibid., 27.

4. See Bradley P. Owens, David R. Hekman, “Modeling How to Grow: An Inductive Examination of Humble Leader Behaviors, Contingencies, and Outcomes,” Academy of Management Journal 55:4 (2012): 787-818; Owens, Michael D. Johnson, Terence R. Mitchell, “Expressed Humility in Organizations: Implications for Performance, Teams, and Leadership,” Organization Science 24:5 (2013): 1517-1538.

5. Owens, Johnson, Mitchell, 2013: 1517.

6. Ibid.: 1518.

7. These traits include modesty, anti-narcissism, openness to experience, honesty-humility, learning goal orientation, and core self-evaluation. None of these traits fully capture the threefold definition of expressed humility. Table and tests for distinctions found in Ibid.: 1521-1524.

8. Ibid.: 1528-1532.

9. Owens, Hekman, 2012: 801.

10. Ibid.: 802.

11. Ibid.: 806-807.

12. For example, see Laurie Goodstein, “A Top Mormon Leader Acknowledges the Church ‘Made Mistakes’,” New York Times (Oct. 5, 2013): http://www.nytimes.com/2013/10/06/us/a-top-mormon-leader-acknowledges-the-church-made-mistakes.html?_r=0; David Usborne, “Mormon Leader Dieter Uchtdorf Says Church Has ‘Made Mistakes’,” The Independent (Oct. 6, 2013): http://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/americas/mormon-leader-dieter-uchtdorf-says-church-has-made-mistakes-8862663.html; Peggy Fletcher Stack, “Uchtdorf Urges Questioning Mormons to Return,” The Salt Lake Tribune (Oct. 5, 2013): http://www.sltrib.com/sltrib/news/56962132-78/lds-church-conference-women.html.csp

13. Dieter F. Uchtdorf, “Come, Join With Us,” General Conference, Oct. 2013 (emphasis mine): http://www.lds.org/general-conference/2013/10/come-join-with-us?lang=eng

14. Ibid.

15. See Nathaniel Givens, “Fiona and Terryl Givens Discuss Uchtdorf in NYT,” Difficult Run (Oct. 9, 2013): http://difficultrun.nathanielgivens.com/2013/10/09/fiona-and-terryl-givens-discuss-uchtdorf-in-nyt/

16. Elder Holland’s talk was similar in nature. See his “Like a Broken Vessel,” General Conference, Oct. 2013: http://www.lds.org/general-conference/2013/10/like-a-broken-vessel

17. Terryl L. Givens, People of Paradox: A History of Mormon Culture (New York: Oxford University Press, 2007), 8.

18. Ibid., 29.

19. David Whitmer, interview by William H. Kelley and George A. Blakeslee, Sept. 15, 1881, Saints’ Herald, Mar. 1, 1882, 68.

I really like this. I’ve often thought about how is it that I can work on my own humility, something I certainly need to work on. However, being humble seems like it’s just something you are, not something you can do or become. But being more appreciative of others and becoming more teachable is something I need to ponder.

Liked the Good to Great reference as well.

I too was moved by the humility, candor, and pleading of President Uchtdorf (and I’m inclined to believe, without any empirical consideration and little more than a handful of personal anecdotes, that part of it has to do with his European [albeit heavily American-influenced] origins and the subtle but very real differences between instances of the Church on either side of the Atlantic). I also admit, however, that, as interesting as I found the research on humility, I am quite uncomfortable with the comparison. This is not a negative critique of the merits of including such a study, but merely a personal conviction that the characteristics which define success in profit-making SHOULD be very different from (if not outright opposed to) the characteristics which define prophet-making. (Cue the critiques about ‘the corporate Church’…) Thanks for the interesting take on what was undoubtedly (no pun intended) an unusual conference address!

I’m glad you liked the post, the I found the following curious:

“…but merely a personal conviction that the characteristics which define success in profit-making SHOULD be very different from (if not outright opposed to) the characteristics which define prophet-making. (Cue the critiques about ‘the corporate Church’…)”

While engaged employees leads to higher productivity and typically higher profit, the point was that leader-expressed humility creates more fully engaged members of the organization. This can translate into a number of outcomes depending on the type of organization (i.e. for-profit, non-profit, church, etc.). But I’m not sure *why* the characteristics “SHOULD” be different. If we assume that profit is inherently dirty or immoral, then sure: they should be different. But I don’t think that is a justifiable assumption.

…but I found*

Pingback: The Marriage of Heaven and Hell: Business and Theology | Times & Seasons